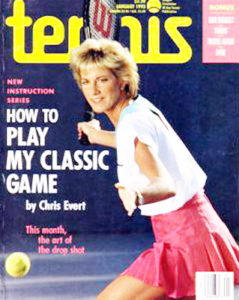

“20 Questions:

Exclusive Interview with Steve Flink

about the career of Chris Evert”

Throughout her career, Chris Evert deferred many press conference questions to a knowledgeable tennis historian and friend who was second only to Evert herself in how many of her matches he had seen, and who surpassed Evert in memorizing the details of those matches, and the record-breaking results they spawned. That man is Tennis Week senior correspondent, former columnist and editor at World Tennis magazine, and recent author of The Greatest Tennis Matches of the Twentieth Century, Steve Flink.

“Steve Flink knows all of my statistics…TENNIS statistics!” Chrissie has joked.

We are very honored and fortunate to have the pleasure of this exclusive and in-depth talk on all aspects regarding Chrissie’s career with Steve, who was often found in Evert’s friends box when he wasn’t in the commentary booth.

I encouraged Steve to disregard the usual editorial restraints of brevity and embrace the informal nature of this format of questions, to provide our readers with what they want: a full-length conversation on many of the issues most-inquired about by ChrisEvert.Net visitors! He has done a remarkable job.

And now, here’s the interview…

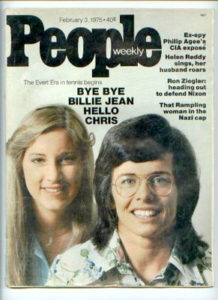

Q-1: During the mid-70s, Chrissie —like many players— skipped the French Open for 3 years to play in Billie Jean King’s spearheaded World Team Tennis events. During those years, Chris was the #1 world ranked player and in the midst of a 197-1 match record on clay between 1973-1981. Being that she was undefeated on clay for 6 years during the skipped FO years, she stood a good chance of taking all 3. (Evert lost only 8 sets during the 125-match winning streak on clay, and won 71 sets by the score of 6-0. She also won all 3 of the US Open crowns played on clay during that winning streak, in 1975/76/77). Meanwhile, in the final calculation, Martina won 9 Wimbledons and Evert won 7 French Opens.

Do you think Chris has regrets about skipping those years at the French, as her fans surely do? And in fairness, do you consider the exposure tennis received with American audiences (who bolstered women’s tennis to greater prominence worldwide) through the WTT events to be worth the sacrifice to her recognized personal achievements in the record-books?

SF: To be sure, Chris would have won at least two and possibly three more French Opens between 1976 and 1978 when she was involved with World Team Tennis. But I don’t believe she really regrets missing those years. At the time, all of the leading women— King, Goolagong, Wade, etc.— were all playing WTT so it was essential for Chris to join them in that venture. Yes, she did win an astounding 125 matches in a row on clay from 1973 to 1979 so that was the time when she played some of her finest ever clay court tennis. But she would have gained no pleasure from staying away from WTT to win at Roland Garros without the challenge of competing against the best players in the world. In turn, she was enormously gratified to come back in 1985 and 1986 to take her sixth and seventh titles at the French over Martina with stirring three set wins. That more than made up for missing the event from 1976-78.

Frankly, she was considerably more regretful about not winning

more than three Wimbledon singles titles. Playing in the final on Centre Court no fewer than ten times and coming away with only three crowns was frustrating in many ways. She knew she was not quite ready when she lost her first final to King (6-0, 7-5) in 1973. That loss was relatively easy to accept. But then, after winning in 1974 and 1976 (the latter was one of her finest grass court displays ever in defeating Goolagong 6-3, 4-6, 8-6 after trailing 0-2 in the final set), she had some tough final round losses. She knew she should have beaten Martina Navratilova in the 1978 final but she did not exploit a 4-2 final set lead and the match slipped away. In 1979, Martina outplayed her to win in straight sets after Chris had beaten Navratilova 7-5, 5-7, 13-11 (saving three match points) in a magnificent match in the finals of Eastbourne the week before Wimbledon.

There is more. In 1980, Evert beat Navratilova in the Wimbledon semifinals after losing their previous four clashes. That win felt like a final. After she came from behind to take that encounter in three exhilarating sets, she was beaming. She was delighted and proud to have prevailed and she fully believed she was going to take the title. But she had a letdown and lost the final to Goolagong in straight sets. She was unable to rouse herself in the fashion she had against Martina. After winning her third Wimbledon in 1981 without losing a set across that fortnight, she lost another tough three set battle with Martina in the 1982 final, and then lost to Martina again in straight sets in the 1984 final when Martina was on her way to a record 74 match winning streak. Considering that Martina had beaten Chris 6-3, 6-1 in the French Open final the month before, her showing at Wimbledon was uplifting as she raced to a 3-0, two service break lead before bowing 7-6, 6-2.

In any event, her seventh and last loss in a Wimbledon final was in 1985 against Navratilova again. She had defeated Martina in their classic French Open final after losing 15 of their previous 16 meetings, so she was clearly on the ascendancy. And she won the first set of the Wimbledon final before bowing. That was the fifth time she had lost to Martina in a Wimbledon final, with three of those showdowns going the full three sets.

So there is no doubt in my mind that her larger regret is not winning more Wimbledon titles. It was great to get to that many finals and a tribute to her flexibility and determination, but she thought she should have won at least two more championships. Graciously, she concedes that she was fortunate to win her first Wimbledon title in 1974, when she defeated Kerry Melville Reid in the semifinals and Olga Morozova in the finals. King lost to Morozova in the quarters and Reid upset Goolagong in the same round. Her task undoubtedly would have been much tougher had she confronted either of those two great grass court players. But the fact remains that she had decidedly more bad luck rather than good breaks on those lawns.

She won a record seven singles titles on the Roland Garros clay, so not winning more was a relatively minor concern. Wimbledon is another story. She was victorious in seven of nine finals in Paris, and succeeded in six of nine at the Open. In turn, she lost seven of ten championship matches at Wimbledon and four of six at the Australian Open (three of those defeats were on the grass, one on hard courts). The bottom line is she was a superb big match player and probably deserved more triumphs on the sport’s most renowned stage.

Q-2: The WTA rankings were not made official until November 1975. The ‘official’ count of her weeks at #1 is 262. But there are a number of factors at work that obscure legend from fact. In 1974, she won 2 Grand Slams (Wimbledon and the French), had a 103-7 match record (only 3 players in history ever had a 100 match winning year, still true to this day – Evert, Court, & King), and had a 56-match winning streak that lasted as a record for 10 years.

Q-2: The WTA rankings were not made official until November 1975. The ‘official’ count of her weeks at #1 is 262. But there are a number of factors at work that obscure legend from fact. In 1974, she won 2 Grand Slams (Wimbledon and the French), had a 103-7 match record (only 3 players in history ever had a 100 match winning year, still true to this day – Evert, Court, & King), and had a 56-match winning streak that lasted as a record for 10 years.

Naturally, most experts picked Chris as the world #1 – John Barrett, Rino Tommasi, and Lance Tingay, who went for Evert-King-Goolagong. But Bud Collins was the only one who didn’t rank her #1 (choosing King-Goolagong-Evert) and it would seem very clear that he was doing everything to promote the fledgling WTA tour. The WTA rankings then used his as the ‘official’ word.

So the pre-computer years appear to hold quite a surprise for Evert fans: Some statistical whizzes, who likewise have a healthy understanding of the history of the sport and knowledge about the ranking system in its various incarnations, calculate that she has 60 more weeks at #1 than she is credited with –from July 6 after Wimbledon 1974 through the first half ‘75 until July (when BJK would have regained it) through September. Then 8 more weeks following her 1975 US Open victory, all before official rankings were counted–This puts her at 322 weeks at #1, only 9 short of Navratilova. It is feasible within that count that she is even closer; the stats were calculated by Navratilova fans, so it was doubtfully overly generous to Chris!

Do you recall your and Chris’ opinion in 1974 about this matter?

Since these types of statistics are often used to judge a players overall career quality, do you think issues like these would bother Chris in how her legacy may be perceived in hindsight in comparison to other great champions? Is there any chance that these weeks will ever be back-calculated by the WTA for the sake of the recordbooks?

SF: Only one thing really mattered to Chris Evert on the subject of the world rankings: she wanted to finish the year at No. 1. Her total number of weeks at the top on the WTA computer was a distant concern at best. And that is true of all great players. Pete Sampras finished six consecutive years (1993-98) at No. 1 in the world on the ATP computer and also set a record with 286 total weeks at No. 1. He never mentions the latter but always talks about the former achievement. Chris was never preoccupied with the weeks she held the No. 1 position because she realized that to be the No. 1 player from the middle of one year until the middle of the next was meaningless; only the year-end figures mattered. To the vast majority of experts, she finished seven years (1974-78, 1980-81) at No. 1 in the world, which is a substantial accomplishment.

There is no question that the introduction of the WTA computer rankings coming as late as November 1975 worked against Chris. To be sure, she would have celebrated another 50 to 60 weeks at No. 1, but would that have made any difference in terms of her place in history? I doubt it. Seven year-end No. 1 rankings is a much more important claim. As for 1974, it is absolutely true that Bud Collins was the only major authority to not place Chris at the top. Not only did experts like John Barrett, Rino Tommasi and Lance Tingay rank Chris at No. 1, but World Tennis and Tennis Magazine did as well.

I remember interviewing Chris at Hilton Head during the World Invitational in October of 1974 and asking her for her take on the rankings in light of her 55 match winning streak, her two majors at Paris and Wimbledon, and her brilliant overall record which ended up at 103-7. She did not have a strong opinion on that topic. She had great respect for Billie Jean and said she would have had no problem with being ranked behind her. When I told her our panel at World Tennis was almost certain to rank her No. 1, she simply smiled and said, “Well if you guys want to rank me No. 1, I won’t argue with you!” She was certainly not consumed by the ranking.

This is not an issue that would bother Chris in terms of her legacy— not at all. And, frankly, most serious tennis historians put very little weight on how many weeks a player held the No. 1 ranking. The WTA will never do anything about those weeks because they would not want to have to wander into a subjective area like that. But, as I see it, none of that really matters. Chris Evert’s place in history as one of the best ever is beyond question. Her record speaks for itself and she will be given the highest of marks for staying at or near the top for nearly two decades.

Q-3: Back to Chris’ 125-match winning streak on clay. It ended in 1979 Rome to Tracy Austin, most heartbreakingly by the score of 7-6 in the third set. Do you know details about the unfoldment of this match and those final points, since most will never see it and will only imagine the pressure of that single match point, with Evert’s six years of unbeaten play on clay surface court on the line?

Q-3: Back to Chris’ 125-match winning streak on clay. It ended in 1979 Rome to Tracy Austin, most heartbreakingly by the score of 7-6 in the third set. Do you know details about the unfoldment of this match and those final points, since most will never see it and will only imagine the pressure of that single match point, with Evert’s six years of unbeaten play on clay surface court on the line?

SF: I was not in Rome for that amazing match with Evert and Austin, but I do know this; Chris led 4-2 in that final set and had a point for 5-2. Laurie Pignon of the Daily Mail was there and he wrote for World of Tennis 1980, “The turning point came when Mrs. Evert Lloyd failed to hold service for 5-2 in the final set.” He also wrote that Chris “pulled back from 1-5 to 4-5 in the tie-break” before losing that sequence 7-4. She said at the time of her 125-match winning streak coming to an end, “Not having the record will take some pressure off me, but I am not glad to have lost it.”

As Pignon pointed out, that match lasted nearly three hours and featured some strenuous 40 stroke rallies. That 1979 season was when Tracy was coming on strong at 16 and it was the year Chris married John Lloyd. They had actually had their wedding on April 17 so it was an emotional time for her. The Austin match was May 12. She had also lost to Austin at the Avon Championships in New York for the first time in March before defeating Tracy at Carlsbad, California so the rivalry was emerging. Over the summer, she beat Austin at Mahwah, New Jersey in the final on the eve of the Open but lost 6-4, 6-3 in the U.S. Open final. That was the first of five consecutive losses she suffered against Tracy before she turned the tables in the 1980 U.S. Open semifinals. I still believe that was the single biggest win of her career.

Q-4: Tracy’s rivalry with Chris is one of the most enigmatic of the Open-era. While Chris’ h2h with Austin was 8-9 total, she lost a full 4 of those matches to Austin in a brief 4-month period following her 1979 disappointment to Austin in the US Open final, and the loss in Rome was her only loss to Tracy on clay surface court. Any thoughts of interest on this unusual rivalry, psychologically or in terms of the flow of their match history?

SF: It was often said that Tracy was the mirror image of Chris. She, too, had extraordinary mental toughness, immense discipline, and unrelenting consistency and depth off the ground. You put your finger on one of the keys to why Chris ended up with an 8-9 career-record against Austin. She lost to Tracy in the 1979 U.S. Open final. She was going for her fifth straight Open title and had demolished Billie Jean King 6-1, 6-0 in the semis. Furthermore, she had just beaten Tracy in the finals at Mahwah, New Jersey in three sets. But she got very down on herself in the Open final and it really stung. Then she lost to her again indoors at Stuttgart and lost a match which was similar to the Open (6-3, 7-5). Tracy had won 6-4, 6-3 at the Open.

At the start of the next season, she lost to Tracy three times in eleven days including twice at the Year-End Championships in Washington, and at Cincinnati in the final. In those three matches, she won only ten games in six sets and it was demoralizing. She wisely decided to take the rest of the indoor circuit off and returned in the spring on the clay with renewed spirit. She won the French Open, got to the final of Wimbledon beating Navratilova, and did not play Austin until the semifinals of the U.S. Open. It was crucial that she had time to rise up to that seminal moment, and she did just that. After losing the first four games of the first set, she got her teeth into the match and lost the set 6-4. Then she started swinging much more freely, going more for the lines, and exploiting her excellent forehand drop shot. Chris won 16 of the last 20 games to close out a 4-6, 6-1, 6-1 victory and it restored her pride.

After that match, she went into the referee’s office underneath the old stadium and grandstand and called her father. She got on the phone and said, “Dad, I won!”, and then burst into tears. She handed the phone to her mother and said, “Tell him I need him to come up for the final.” Jimmy Evert flew up that night and was there for the final the next day when she beat Hana Mandlikova for her sixth Open crown. But the win over Austin was what really mattered.

So my take is that Chris needed to come to terms with Tracy’s game and taking the winter of 1980 off was one of the best decisions she ever made. She recovered her enthusiasm for the game and gave herself time to deal with the special challenge of Austin. Not since Nancy Richey in her teenage days had Chris confronted someone who could stand toe to toe with her from the backcourt and match her consistency, depth, discipline, and concentration. But remember that it all changed with the 80 Open. The next year Chris defeated Austin in their classic at the Meadowlands in a third set tie-break, and in 1982 in their last match in the same building, she took apart Tracy 6-0, 6-0.

Clearly, when Tracy first burst upon the scene, Chris was too  strong and experienced for Austin and she won easily over Tracy at Wimbledon in 77 and the US Open in 78. Tracy started giving Chris problems in 1979 when she had her first win over Evert at Madison Square Garden, ended the 125 match clay court winning streak, and stopped Chris in the U.S. Open final. In that stretch, she was a player rapidly on the rise and Chris lost some of her edge after five straight years at No. 1 in the world. That was all about timing; Chris did not want it as badly as Tracy did, and Tracy was ready to take on the world.

strong and experienced for Austin and she won easily over Tracy at Wimbledon in 77 and the US Open in 78. Tracy started giving Chris problems in 1979 when she had her first win over Evert at Madison Square Garden, ended the 125 match clay court winning streak, and stopped Chris in the U.S. Open final. In that stretch, she was a player rapidly on the rise and Chris lost some of her edge after five straight years at No. 1 in the world. That was all about timing; Chris did not want it as badly as Tracy did, and Tracy was ready to take on the world.

At the end, Tracy was hindered by injuries (primarily her back) and could not offer the same resistance, but Chris was no longer psyched out by Austin. That is how I read it. Chris would have had the career edge had she been able to play Tracy a few more times in 1982, but they only met at the Meadowlands and nowhere else.

There is no doubt in my mind that Chris was the superior player. She had more variety off the forehand because she could take high balls and slice them down the line and she could hit the inside-out sidespin forehand better than anyone. Her serve was better than Austin’s, and even her two-hander was slightly better in my view. She lost many of those matches to Tracy before she walked on the court and Tracy deserves credit for that since she put so much of that apprehension inside of Chris, and then fully took advantage of it on the court.

We will never know what Austin might have accomplished if she could have continued playing top-flight tennis for longer. I am sure she would have won four to six more majors along the line, but the trauma for Chris would have been over. In fact, Chris started working with Dennis Ralston in 1981 and he helped her a great deal as she improved her second serve (adding more kick) and started coming to the net with more confidence. She was a more complete player from 1981 on, but she was unable to put that fully to the test against Austin because they met so infrequently. If Chris had played Austin during her mid-80s period, she would have won probably 70 percent of the matches because she would have had more options.

Q-5: Little known 70s moment: When Chris played Martina for the 1975 US Open semifinal, which she won, they both walked onto the court knowing that Martina was going to seek political asylum in the United States after the match. How could that kind of dramatic knowledge not been a distraction from play? And can you just illuminate the drama of that match with any memories of the press or anything regarding the time of the defection?

SF: The Evert-Navratilova 1975 US Open semifinal was held early in the day, either late in the morning or perhaps around noon. Chris won 6-4, 6-4 on the clay and used her usual recipe of breaking down Martina’s backhand with a barrage of deep and accurate ground strokes. Chris trailed 2-4 in the second but sealed four games in a row for the win. As for the background of it all, Martina made her announcement two days later on the day of the men’s final so I am sure it was uppermost on her mind. But did it have any bearing on the outcome of her semifinal with Chris? I seriously doubt it and I saw the entire match. Chris was 11-2 lifetime over Martina at that stage and despite two losses indoors during that year, she was still a much better player, and much more sure of herself on the big occasion.

Chris was all business as always, playing her brand of clay court tennis, forcing Martina into mistakes, controlling the tempo of the match. Martina did not play badly and both sets were competitive. Martina did lose her cool a bit at the end. Chris was serving at 3-4, 30-15 and hit a lob that Martina thought was long. The linesman disagreed and Martina did not win another point in the match.

In any case, World Tennis wrote, “Martina Navratilova’s decision to request asylum from the U.S. came as no surprise to close observers of the women’s tennis circuit; it had been strongly rumored for the three previous weeks that the move would come during the U.S. Open.”

Q-6: At the same age when Steffi Graf was putting down her racquet and retiring, Chris was making the decision to put down her WOOD racquet and take on a whole new challenge in adjusting to a graphite racquet, and the new nature of tennis, to better challenge Martina Navratilova. Does it not seem that Chris’ being 2 years older than Martina and having already spent 7 years at #1 before Martina started truly dominating the game in 1983 is an unacknowledged reality in assessing the contests between the two players in the 80s? For Martina, this kind of dominance was new and exciting and she had everything to prove. Psychologically, the barrier for Evert to overcome that, after already having lived in tennis’ spotlight for so long, seems beyond immense.

Is there some level at which you suspect Chris unconsciously liked being the #2 underdog, rather than always having to be expected to win?

SF: You make an entirely valid point about the relative hunger and motivation of both Martina and Chris and how that had a bearing in their contests during the 1980’s. The two-year age gap was of some significance; the seven-year run of Chris at No. 1 was a larger factor. Martina was just coming into her own in 1982 and she had a whole lot more to prove. Remember that coming into the 1978 Eastbourne final, Chris held a commanding 20-4 lead in their rivalry.

To be sure, Chris had lived in the spotlight for much longer. I think there is some truth that Chris may well have taken comfort during the 1980’s when she was constantly ranked second behind Martina. In 1982, she made a stirring bid to wrestle the No. 1 ranking away from Martina by winning the U.S. and Australian Opens. Had she knocked off Martina at the Meadowlands in the year-end Championships, she might have garnered another No. 1 ranking. But by 1983, it was too much for her in some respects. The drive to remain No. 1 and do so for seven of eight years between 1974 and 1981 had been no mean feat. She put an incredible amount of pressure on herself to be the best player in the world over that span. Martina, meanwhile, loved the opportunity to show her finest colors to the world after living in Chris’s shadow for so long. And Chris understandably did not have the same confidence or conviction. In that phase, it was not as all-consuming as it had once been.

Q-7: There was a period during the transition of the wood racquet to graphite, where Chris and Martina played 10 times, with Martina racking up 9 h2h victories. Nowadays, it is clear that if the top two players face-off and one has a wood racquet, her chances will be greatly diminished, but it was not so obvious at the time that this was playing such a major factor in the results. Then, after switching, Chris seemed to gain more and more confidence as she progressed in Grand Slam finals against Martina using her graphite racquet in 1984: a terrible showing at the French, a remarkable 3-0, 2-break lead at Wimbledon but still losing in a close match, followed by the 3-set final at Flushing Meadow where Chris almost won, until she finally beat Martina in January proceeding the victory in Paris 1985.

Do you think this was an issue of Chris slowly creeping up in ABILITY or rather an inner issue; a matter of confidence growing with each match? It seemed for a while Chris walked out simply believing she couldn’t win, and didn’t. The perfect example perhaps being her demolition of Mandlikova in the 84 Wimbledon SF, then picking up where she left off at the start of the final against Martina. Mandlikova and Navratilova were not so dramatically far apart as serve and volleyers, but Chris walked on court confident she would destroy Hana, whereas she seemed almost too surprised to be doing the same against Martina, and let the 2-break first-set lead slip, reverting to the familiar ground of taking second place. Is it a fair suspicion that Chris’ PERCEPTION of Martina’s ability was as strong a determinant of their h2h results in ‘83/’84 than Martina was? (I’ve seen this issue of Chris’ perception of her ability to win determine the factors in matches so many times…especially if someone said something she didn’t like, and went out to prove a point.)

SF: Chris needed some time to adjust to her new graphite racket in 1984 but I do not place too much stock on that in reflecting on  what happened against Martina in that period. Navratilova from 1982-86 won 70 of 84 tournaments and lost a mere 14 matches. Chris did a great job to beat Martina in one Australian (1982) and two French finals during that stretch (1985 and 1986). Was she at a disadvantage by sticking so long with the wood racket? I don’t believe so. She beat Martina with that racket in the 82 Australian final and played top notch tennis to win the 1982 U.S. Open with the wood.

what happened against Martina in that period. Navratilova from 1982-86 won 70 of 84 tournaments and lost a mere 14 matches. Chris did a great job to beat Martina in one Australian (1982) and two French finals during that stretch (1985 and 1986). Was she at a disadvantage by sticking so long with the wood racket? I don’t believe so. She beat Martina with that racket in the 82 Australian final and played top notch tennis to win the 1982 U.S. Open with the wood.

I believe she adapted very well to the graphite. Chris had seldom been at her best in 1983 but that was more about her state of mind than the state of her tennis. In 1984, she was more excited about the competition. Nevertheless, despite the benefit of the graphite racket, she lost six straight times to Martina in 1984. To be sure, it was getting closer and closer over the course of that year from Paris to Wimbledon to the U.S. Open, where she came agonizingly close to a victory. After losing that Open final 4-6, 6-4, 6-4, she was in tears and told me, “That would have been the perfect match to retire on.” But that led to her big wins in 85 and 86.

By 1985 and 1986, Martina was the burdened player trying to protect her turf at No. 1 and wondering if she could possibly sustain her standards. Chris was now the more motivated and driven player. They had reversed roles in some respects and Chris enjoyed rising up to the challenge of toppling Martina in some very big matches. It really carried her through the rest of her career, and in 1988 she beat Martina in the semifinals of the Australian Open on hard courts in one of her finest late career performances (6-2, 7-5). Then she took Martina apart on clay in Houston 6-0, 6-4 and those back-to-back wins marked the first time in eight years that she had defeated Navratilova twice in a row.

There is no doubt that there were indeed “inner issues” for Chris when she took on Martina in 1983 and 1984. It did reach a point where she did not believe she could beat her anymore. When I spoke with her about the 1985 French win and how she managed to hold on from 5-5, 0-40 in that final set to record that victory (6-3, 6-7, 7-5), she made some fascinating comments: “Nobody gave me a chance going into that match. I don’t think people thought it was going to be an epic Evert-Navratilova match. When I won, it was the happiest I have ever felt after winning a Grand Slam title. I was thirty at the time and everybody had counted me out. Beating her near the end of my career, when everybody including myself was beginning to doubt I would ever do that again, was very rewarding. I beat the odds and broke through my negativity. Winning that title spurred me on. That title also prolonged my career for another four years. I honestly have never felt better after winning a tennis match.”

That comment tells you how much psychological baggage she had been carrying around for the preceding two years. She really had stopped believing against Navratilova. I would say it was partly her perception that Martina was too good and partly the reality of just how good Martina had become. But she dealt with that admirably and refused to give up. Many other players would have been permanently shattered by the 84 Open loss. She had the crowd with her that day, she was playing inspired tennis, and Navratilova was nervous. But Chris still lost. And yet, she made up for that the next two years because her psyche had changed, her confidence came back, and she was undoubtedly the toughest player ever mentally in the history of the women’s game.

Q-8: In the re-match following Chris’ 1971 US Open SF confrontation with Billie Jean King, CBS billed the final in TV Guide as the ‘Match of the Year… Comeback Kid: King vs. Evert’ and Chris won 6-1 6-0. People were lined up for blocks in Ft Lauderdale…on roofs, on cars. Chris does not mention this match often, but do you suppose it is up there as one of the most important in her early career, alongside beating Margaret Court when she was 15 years old?

Q-8: In the re-match following Chris’ 1971 US Open SF confrontation with Billie Jean King, CBS billed the final in TV Guide as the ‘Match of the Year… Comeback Kid: King vs. Evert’ and Chris won 6-1 6-0. People were lined up for blocks in Ft Lauderdale…on roofs, on cars. Chris does not mention this match often, but do you suppose it is up there as one of the most important in her early career, alongside beating Margaret Court when she was 15 years old?

SF: The match Chris played against King early in 72 which she won 6-1, 6-0 was something that meant a lot to her at the time because it was so emphatic and it proved she was far superior to Billie Jean on clay. But because Chris kept improving rapidly it was not one that the press or even Chris herself talked about for long. The Court win was far more significant since Margaret had only weeks before completed her mission by winning the Grand Slam, becoming only the second woman to pull off that feat. Margaret was a lot more comfortable on clay than Billie Jean— she won five French Championships/Opens including a win over Chris in the 1973 Roland Garros final— and it was a two tie-break win for Chris so that gave it greater importance as well since Court clearly was in it from start to finish. The King win in Florida was satisfying and it was a signal to Chris that on slow courts she could make great players look bad.

Q-9: One of Chris’ lesser-known nicknames, alongside her more notorious “Chris America” and “The Ice Princess” labels, was the moniker of “The Double Bagel Queen”, certainly for dishing them out so often, not for eating them. She double-bageled more players than anyone ever will again and did so to the best in the history of the sport; Martina in ’81 & Tracy Austin in ’82, all without ever being double-bageled herself (worse pro loss was 6-0 6-2, which only happened twice). Then there were MANY such close calls against all-time greats; beat Billie Jean King SIX times without losing more than 2 games, Rosie Casals EIGHT times without losing more than 2 games, Francoise Durr FIVE times without losing more than 2 games, Virginia Wade SIX times without losing more than 2 games; then Jaeger 6-1 6-0 in her prime years at the 82 Aussie Open, Hana Mandlikova 6-1 6-1 at the 86 French, Manuela Maleeva 6-1 6-1 at Amelia in ’84 & 6-1 6-0 at Key Biscayne in ‘86; and over Martina again with a 6-1 6-0 win in the ’75 Italian Open final proceeding their 3-set Championship match in Paris a month later.

Can you identify what aspects of Chris’ game allowed her to steamroll the best players in history like that? In viewing her matches, were you able to actually sense early in a match that she was going to key-in to a bagel frenzy?

SF: The reason Chris won so many one-sided 6-0, 6-0 or 6-0, 6-1 matches was the combination of her temperament and her unparalleled ball control. It all went hand in hand to enable Evert to demolish other great players. Even as her game changed during the 1980’s and she improved her second serve, added a topspin lob off the forehand, began picking up the pace of her ground game, came in more and developed a sounder volley and a stronger overhead, even after all that, she remained astonishingly consistent from the backcourt. Because she measured her ground strokes so well, she always played within herself and did not give anything away. At the same time, she was relentlessly probing, forcing her opponents into errors, finding their weaknesses and exposing them unswervingly. She was as good a match player as the women’s game has ever known.

She did not spend that much time in advance of matches plotting strategy. It was more a matter of letting her instincts guide her and figuring out what to do when she was out there in the heat of the battle. What makes her collection of routs so amazing is that they came against such different types of players. Wade, Casals and King were the serve-and-volleyers who gave her a nice target which she enjoyed; Martina was Martina and even on clay that was a phenomenal 6-0, 6-0 dissection at Amelia Island; and to do that to Austin and even Jaeger who were so proficient themselves as baseliners was an extraordinary feat.

It was not a single aspect of her game that enabled Chris to record these nearly impeccable displays. Rather, it was the entire package of precision, concentration, determination, quiet intensity, and an inordinately astute mind. I can’t say in watching her play hundreds of times across the years— I never missed a match she played at the U.S. Open, Wimbledon, or the French Open— that there was ever an obvious clue that it was going to be one of those days when she would not lose a game or come through 6-0, 6-1. I would not necessarily see it coming, and yet it never surprised me because she was so cool and calculated, so unerring, and so good once she built a lead. In many ways, the one that surprised me the most was the 6-0, 6-0 semifinal win over Austin at the Meadowlands in 1982. In fairness, Tracy was a long way from where she had been a year earlier when she played a classic against Chris which Evert won in a third set tie-break on the same court. But, regardless, to not lose a game against a player who had so many similar traits with such a solid ground game who was also incredibly mentally tough— that was the match that stands out to me among the double bagels.

Q-10: Chrissie hinted to Tony Trabert (in his ‘Sports Legends’ documentary on her) that the things that make a person a great champion are not necessarily the most healthy, positive mental states…and suggested she thought they were often negative motivations. But what great artist is born from ideal conditions? Do you get the sense that Chris resents the internal struggles that brought her to greatness or do you know if she’s revised her position on those issues being worth their weight in sacrifice?

SF: I do not think for a minute that Chris resents anything about how she was raised and why she became a champion. I think she knows that the unsung hero was surely her father, who gave her the framework for success with his emphasis on sound fundamentals. He also told her early on: “Don’t let your opponents know what you are thinking. If they see you getting upset about a call or a point, they will use that to their advantage.” He was a great coach and father and he really shaped her thinking and did a stellar job of molding her tennis and teaching her that tennis matches are lost more often than they are won.

As she reflects on her career, I think she is grateful that it lasted so long and gave her so many rewards. I think what she meant in her  interview with Tony Trabert is that winning can and must be an obsession if you want to be a world champion. If that obsession gets way out of hand and the only way you measure yourself in life is by the nature of your wins and losses on the tennis court, then that can be unhealthy. But Chris knew she was fortunate to have had a great life outside the lines as well that has given her a good deal of pleasure. She always saw herself starting a family and now is the mother of three boys, and is supremely devoted to them and their welfare.

interview with Tony Trabert is that winning can and must be an obsession if you want to be a world champion. If that obsession gets way out of hand and the only way you measure yourself in life is by the nature of your wins and losses on the tennis court, then that can be unhealthy. But Chris knew she was fortunate to have had a great life outside the lines as well that has given her a good deal of pleasure. She always saw herself starting a family and now is the mother of three boys, and is supremely devoted to them and their welfare.

She does not resent the struggles that led her toward greatness because the rewards made it well worth all the sacrifices. Through it all, she kept learning about herself and she came to understand her finer qualities and her flaws. She knows that being a tennis champion and playing for two decades on international stages was crucial in making her what she is today. And she has a healthy perspective on it all. She lives in the present and does not dwell on her past glories in the game. She has thrown herself just as thoroughly into motherhood as she ever did into tennis.

Q-11: Mary Carillo once called Evert “the best small-handed player of all time.” Mary having to pry her hands free of her tennis racquet after a particularly tense match, finger by finger, is legendary. But few of us know what happened, do you know the story?!

SF: Believe it or not, I really don’t know much about this story. But it illustrates how much she held inside herself. She was the cool perfectionist who appeared to be oblivious to pressure but I know how much it bothered her that people looked at her as some kind of robot or machine during her dominant days. And when the fans in 1976 started taking her for granted and often rooted for her opponents, it was very painful.

Q-12: Virginia Wade once said, “The worse thing you can do to yourself is to beat Chris, because the next time she plays you, she goes out of her way to make it her business to really show you who’s boss.” This is a pretty hilarious comment, but holds true under examination. A quick run-through of some of Chris’ loses, and her on-court responses, look something like this: Lisa Bonder upset Evert in Tokyo in ’83 by the score of 7-5, 4-6, 6-4 and Chris countered in their next meeting at the ’84 Italian Open, 6-1 6-1. When Sylvia Hanika scored her first victory against Chris at the 87 Slims Championships by 6-4 6-4, after 15 matches of losses over 10 years, Chris responded by beating Hanika in the follow-up as badly as she ever had in the 10 years prior, 6-1 6-0, at the ’88 Largo Slims. The 1975 Wimbledon SF loss to Billie Jean King by 6-2, 3-6, 6-3 was followed up by a 6-0 6-1 win by Evert, and the list goes on.

The statement also applied a number of times to players who talked AS THOUGH they THOUGHT they could beat Evert; Hana Mandlikova at Wimbledon in 1984 in particular, and Pam Shriver in 1985 at Newport Virginia Slims. In both cases, she was very focused at the start of every point, as though, if she had her way, she would intend to win every single point of the match, and for the most part in those matches, did. (defeated Hana 6-1 6-2 in what the English Press called “a public lynching” and, after being down 2-0 to Shriver at Newport, lost only 3 games the rest of the match, 6-4 6-1 in an unrelenting display of domination on Shriver’s best surface.)

This underscores the highly unusual ability Evert had to rise well above ‘normal functioning level’ when a point needed to be made. Can you think of 3 times when Chris had that hyper-fiery determination to win at all costs where she still failed to win? I think of the 1976 Los Angeles Championships to Goolagong, for one.

SF: This may be your toughest question, because it was rare when Chris was “hyper-fiery” determined that she did not win. I would not put the Goolagong Los Angeles match in 76 in that category. Her confidence was relatively low at that time. She had lost to Goolagong in Philadelphia leading up to The Virginia Slims Championships in Los Angeles, and had struggled on her way to the final. Although it was a top of the line match and both players distinguished themselves, I would not say Chris was at her best technically or mentally. I would put the 84 US Open final in that category because she wanted to win that tournament badly, she had been in good form en route to the final, and it was such a big occasion on Super Saturday. That was why that loss was so hard to take. Another would probably be the 1981 Australian against Navratilova, when she came all the way back from 5-1 in the final set to reach 5-5 but could not finish the job and lost gallantly 6-7, 6-4, 7-5. She gave her all in that one and came up narrowly short.

Wade was on target with her comment. After her last win over Chris at the 1977 Wimbledon in the semifinals, she never beat her  again for the rest of her career. After those two early season losses to Goolagong at Philadelphia and LA in 76’, she beat Evonne in both the Wimbledon and U.S. Open finals. If you beat her, she did not forget it and was a resilient competitor who could always turn things around. She had lost to Seles in the finals of Houston early in 1989 in a well played, three set match and Monica had raised the level of her game after that. So hardly anyone thought Chris could beat her at the Open when they met later that year, and yet she did just that (Evert won 6-0 6-2). I still put that one up there among the top five finest performances of her entire career. Her timing, tactics and tenacity were showcased beautifully in that match and she kept hitting behind Monica off her forehand for winners. She essentially turned back the clock that afternoon.

again for the rest of her career. After those two early season losses to Goolagong at Philadelphia and LA in 76’, she beat Evonne in both the Wimbledon and U.S. Open finals. If you beat her, she did not forget it and was a resilient competitor who could always turn things around. She had lost to Seles in the finals of Houston early in 1989 in a well played, three set match and Monica had raised the level of her game after that. So hardly anyone thought Chris could beat her at the Open when they met later that year, and yet she did just that (Evert won 6-0 6-2). I still put that one up there among the top five finest performances of her entire career. Her timing, tactics and tenacity were showcased beautifully in that match and she kept hitting behind Monica off her forehand for winners. She essentially turned back the clock that afternoon.

In the end, I would select only those two Navratilova losses in your special category. Otherwise, to an astonishing extent, she always seemed to find a way to win when she was in her most determined frame of mind.

Q-13: Here are the career-long strike rates for reaching grand slam finals: Court: 0.62 Evert: 0.61. Graf: 0.57 …Navratilova is 5th behind Goolagong.

Then the Grand Slam WINNING strike-rate (based career-long from the last year a grand slam was won, to account for age, and for historical fairness, minus the Aussie Open which was usually not played by the top players throughout the 70s): Court & Evert are tied at 42%, Steffi Graf is just a breath away on 41% (but with no Monica), Navratilova is at 33%, King is at 29%.

And the most obscene testament to Evert’s strength as all-time great, the strike rate for reaching Grand Slam semis (INCLUDING Aussie Open & until retirement year), career-long: EVERT 0.929, COURT 0.766, GRAF 0.685, NAVRATILOVA 0.677.

How do you look at the issue of the ‘best singles player ever’ discussion? Some people suggest there are simply tiers (Lenglen, Court, Evert, Wills Moody, Navratilova, Graf) followed by (Connolly, Seles, King, Goolagong) etc. – What is YOUR first, second, and possibly 3rd tier on the all-time great female players list?

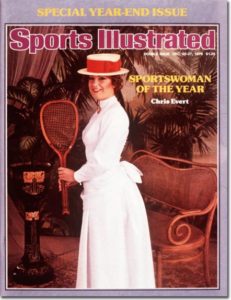

SF: Those success rates for reaching Grand Slam finals are fascinating and compelling. They demonstrate Evert’s striking consistency over a long period of time. Court’s percentage is greatly inflated by the weak fields she played against at the Australian Championships/Open which she won 11 times. Court could have made it to the final of many of those events blindfolded because the competition was so weak along the way. For Chris to make it to 34 Grand Slam finals out of the 56 she played is almost beyond belief. To reach the semifinals of 52 out of 56 majors is something no one else will replicate. She won 18 of her 34 “Big Four” finals, but of the 16 defeats, Navratilova accounted for 10. Clearly, she belongs among the truly elite players of all time.

But when I look at the greatest players of all time and try to rank them, I put much more stock in the majors that they won. As I mentioned, Court’s record is not as good as it looks. So I weigh that, examine the longevity of the players, their consistency, and how they fared against their toughest rivals. Some of it is subjective in the analysis of ranking the best players of different eras; some of it is not. I do not put them in tiers, although I think it is an interesting notion and a valid way of looking at it. I simply examine the totality of their records, their records in the majors, their level of play over a long period of time. I also consider how they did head-to-head against their worthiest rivals.

The success of players reaching Grand Slam finals is significant and a great barometer of their consistency and high caliber play. There is no scientific way to grade the best players in the history of the game. You weigh all of the evidence, consider the good wins and the bad losses, and make a judgment. In my book, “The Greatest Tennis Matches of the Twentieth Century”, I ranked the ten best men and the ten best women of the century. I selected Steffi Graf at No. 1, Navratilova at No. 2, and Chris Evert at No. 3. The rest of the list is as follows: Helen Wills Moody 4, Margaret Court 5, Suzanne Lenglen 6, Maureen Connolly 7, Billie Jean King 8, Monica Seles 9, and Martina Hingis 10.

I made that list in 1999. I would change very little on that list now, although Hingis would surely be replaced by Serena Williams, who may yet rise higher depending on where she goes from here.

I am a big believer that all champions would succeed in any era, that they would move with the times and do what was necessary to win under any circumstances. In the final analysis, I see Graf as the best ever because of her surface mastery— winning every major at least four times— her athleticism, her high standards over a long period of time. She did finish only 9-9 against Navratilova and 8-6 over Evert, although Chris beat her the first six times they clashed.

In any event, Graf was awfully good when it counted the most, and despite her sometimes vulnerable backhand which could be attacked— Navratilova kept coming in on that side behind her serve and backhand approach, while Chris would open up the court by hitting wide to Steffi’s forehand and then drill her two-hander crosscourt to break down Graf’s backhand, or she would do it in reverse and hit the sharp crosscourt two-hander to open up the forehand crosscourt— she had the best forehand I have ever seen among the women, a very underrated serve, astounding foot speed, and steely determination. I place her narrowly ahead of Navratilova, and Martina a shade above Chris.

Chris was a good deal more reliable across her career in the majors and her record of winning at least one Grand Slam title for 13 straight years won’t be touched. The case for her is that she was a better day in, day out, year in-year out player. But Martina not only held a slight edge at 43-37 in their career series, but that included a big edge in major finals: Martina was 2-1 over Chris in Australian Open championship matches, 5-0 at Wimbledon and 2-0 at the US Open. That 7-0 record in Wimbledon/US Open finals is a critical statistic, because those were the biggest matches they ever played. Chris did beat Martina in three out of four French Open finals, which is irrefutable evidence that she was a vastly superior clay court player. Overall, Chris was 11-3 on clay against Martina. Had she managed to defeat Martina in one or two Wimbledon finals, had she prevailed in one of those Open championship matches, it would have been different. She would then have captured more major singles titles and the scales on the big occasions would have been more balanced. As it was, they each won 18 majors.

Let’s consider the breakdown: Martina won 12 of her 18 majors on grass including a record nine at Wimbledon (the world’s premier event); Chris secured 10 of her 18 on clay (including a record 7 French Open titles), took 5 on the grass, won another three on hard courts. Martina was more versatile and complete with her talent. She was not nearly as good as Chris off the ground but had a decidedly better serve and a much better volley off both sides. So for a variety of factors, I have to rank Martina just that notch above Chris. On the other hand, it is my view that Chris is a class above anyone else on the all-time list because no one has played the game that well for so long without interruption. To never miss the quarterfinals of the U.S. Open for 19 consecutive years is a tribute to how she sustained strikingly high standards.

Graf, however, had the most enviable blend of talent, temperament, and achievement. Her 22 majors is to me a whole lot more impressive than Court’s 24. Her 22-9 record in Grand Slam finals is excellent. She finished eight years at No. 1 in the world. In my book, she is the best ever and I do not give her that status lightly. At her best— and she had a good many years when she was near the top of her game— Graf in my judgment was better than anybody else that has played the game. Let’s look at Steffi, Martina and Chris and put them all in a time warp with all three in their primes. Graf would have lost some close clashes to Navratilova on grass, and would have lost some battles with Chris on clay. But, across the board, she would have prevailed in my view. It is a tough call to make but that is how I see it.

Q-14: Some people put a lot of stock in head to head records, but these confrontations often reflect the dynamics of playing style more than reflecting who is a stronger overall player. Kathy Jordan beat Chris 3 times, for instance, while NEVER beating many players Chris never lost to, simply because her playing style had an odd ability to penetrate Evert’s game. Martina meanwhile had loads of trouble with players like Sukova, Mandlikova, Kohde-Kilsch, and Shriver, who Chris customarily plowed through mercilessly (at least, up until Chris was already 32 years of age).

Navratilova’s winning head-to-head with Chris in the latter part of the rivalry may have helped obscure from public memory the reign

December 20-27, 1976

credit: Graham Finlaysonoff

of Evert’s dominant period in tennis between 1974—1981, and given a false sense that Martina was necessarily a better player. Mary Carillo said, “Chris can take a perverse pleasure in the knowledge that the architects of Martina’s game had Chris’ very much in mind, so fine were her groundies off both wings.”

I won’t ask you to choose between Chris and Martina, because it may be accurate to say the difference was merely a matter of who was more ‘on’ during any given day.

But can you think of other rivalries where one player was, in your opinion, a better player but had terrible records against other players for stylistic or psychological reasons? Goolagong had a dreadful record against Billie Jean King, for instance (only 4 wins!) Francoise Durr never beat Court (in 22 matches!) but gave King fits and beat Bueno, Goolagong, Richey, Wade, Turner, and in fact–in 1975–at the age of 33, she stunned Navratilova (then world ranked #2) in the Semis of the Colgate Inaugural Championships 6-1, 6-1!! (then lost to Chris, who she never beat, in the final)

SF: The head-to-head records of the top players are a fascinating subject. Why did Goolagong not do better against King for instance? I think the reason is she was vulnerable in that rivalry because King had more discipline and maintained her focus better. She also exploited Evonne’s suspect second serve and had a far superior second serve of her own. Margaret Court and Durr is another good one, because Durr could come up with the occasional win over King who played her much the same way as Court. But Margaret’s ground game— particularly her forehand—were better than King’s. So she kept pressing forward to make Durr pass with that western backhand, and held her own from the baseline as well.

Kathy Jordan against Chris was something of an oddity. Kathy was tenacious and unrelenting with her serve-and-volley game against Chris at times, and she exploited her inside-out forehand to keep Chris off guard from the backcourt. On the other hand, Chris had inadvertently taken some niacin tablets the night before she lost to Jordan in the third round of Wimbledon in 1983, when she was going for her fourth consecutive Grand Slam title. And she was clearly not herself on the old Court 1 in that match, losing the first set quickly and then squandering a 4-0 second set lead.

So it is the clash of different styles and stylists that makes it intriguing. The Durr win over Navratilova was during a period when Martina was losing too many matches to too many people who should not have bothered her. She lost that first round match to Janet Newberry at the U.S. Open of 1976 before the Durr defeat in Palm Springs. She was badly overweight during that stretch.

Chris Evert had to come to terms with Nancy Richey’s penetrating, flat ground strokes off both sides, particularly the forehand. She lost to Richey the first five times they met before taking the last six. Most of those losses were when she was 14 and 15, including the final of Charlotte in 1970 after she had crushed Durr and Court. Richey presented technical problems for Chris, and even as late as 1975 with Chris at No. 1 in the world and Nancy past her prime, Richey built a commanding 7-6, 5-0, 40-15 lead in the semifinals of the U.S. Clay Courts before Chris staged one of her greatest comebacks ever to win 6-7, 7-5, 4-2, 40-30 retired. Nancy was apparently cramping.

So sometimes it comes down to logical, technical and tactical reasons why some inferior players beat those with larger reputations and records. In other cases, it is psychological. In some cases, both factors contribute to the outcomes.

Q-15: The unquestionable value of head to head clashes is that it DOES create rivalries, even if the better player is not always ahead. On this topic, Steffi Graf and Monica Seles, from a rivalry’s standpoint: It seemed that nature had provided Graf with a fitting foil, to balance the game. There was Chris and Martina; remove one and you have an awful lot of grand slams under one person’s belt. There was Court/King. Williams/Williams. More recently, Blonde Belgium/ Blonde Belgium. How do you think that effects the perception of tennis history in that Graf’s records seem inflated for her playing level. This is not a criticism of Graf but to make the point of removing Martina or Chris from the equation, and the record books go off the charts. She seems untested in comparison.

SF: Graf surely suffered on a number of levels by losing Seles as a major rival— as her premier rival. Monica had overtaken Steffi starting in 1990 when she beat Graf in the French Open final. Monica was only 16. The pity is that the rivalry was coming into its own in the year before Seles was stabbed in the back in Germany in 1993. In the 1992 French Open final they played their best match ever against each other with Monica coming through by the skin of her teeth 6-2, 3-6, 10-8. At Wimbledon that year, Graf crushed Seles at the cost of only three games. Then, in the final of the 1993 Australian Open, they produced a first class contest which Seles won in three sets. About three months later, the Seles tragedy occurred.

It is my belief that the gap had greatly narrowed, and that Graf was gaining ground on Seles. They would have had a spectacular series of matches had Monica not been taken out of the game by such misfortune. But was Graf untested as a result? Perhaps, but perhaps not. She had some stupendous battles with Sanchez Vicario, including an epic at the 1996 French final which Graf won 10-8 in the third. And after Seles came back after nearly 28 months out of tennis, Graf beat Seles in a terrific three set match in the finals of the U.S. Open after Seles had returned triumphantly at the Canadian Open.

A case can certainly be made that Graf’s record was inflated by the absence of Seles, but the fact remains that she had to deal with other rising players. Like Chris and Martina, Steffi had a long run, playing pro tennis from 13 to 30, winning her first major in 1987, taking her last in 1999, beating a wide range of formidable players all through her career. So you can’t really penalize her for Monica not being on the scene for a few years. I do agree that both Chris and Martina would have won a ton more Grand Slam events had they not needed to keep going through each other to take the big prizes. Venus Williams might have won nine majors by now if Serena had not beaten her in five out of six Grand Slam championship matches in 2002 and 2003. Billie Jean might have picked up a few more without Margaret Court beating her in 22 of 34 career showdowns.

But I do not place too much emphasis on what might have been over the record and what it represents.

Q-16: This is a question regarding the wood racquet era during which Chris was so dominant in contrast to today: Has tennis ‘evolved’ and become a better sport if there are so many injuries (harmful to both player’s bodies, their momentum, the sport’s rivalries, and a tournament’s ability to draw top players on a consistent basis) and is it a better sport if the technology of the sport does the work for the player of creating pace and accuracy, winning more often with sheer force than the aspects of the game that develop them as people: patience, thought, willpower, and working through points instead of blasting through points?

Martina Hingis made a very fascinating (to me) comment on her Tennis Channel interview recently, and I am quoting her: “Professional sports isn’t the healthiest thing in the world”. The motto that tennis is a ‘sport for a lifetime’ was always assumed to be a given. But there are so many injuries with today’s game, the health of the sport has to be shroud in some degree of question. The 100-player open letter by past champions to the ITF at the 2003 Wimbledon asking that racquet size and weight be limited for pros seems to not only be an issue of using tools that create an interesting sport with diverse playing styles, but of protecting players from the sport they are inheriting, which currently has no protective guidelines.

How do you feel about the power-direction of the sport changing tennis’ character, but also putting players at risk for potential long-term injury, possibly asking more from player’s bodies than they’re designed to take? Wasn’t it crucial to Evert’s long-standing consistency (and definition as a champion) to not have the guidelines of the sport exposing her to injury?

SF: This topic would take us too many weeks to cover thoroughly, and even then we might not get to the bottom of it. There is no doubt that the game has become increasingly physical. I think those who are not willing to call tennis a contact sport don’t know what they are talking about. The injuries on both the men’s and women’s tours have been mountingly alarming in recent years. The trainers are more sophisticated than ever, the players do extensive work off the court to stay in shape and prevent injuries, and yet they keep getting hurt.

Is this all a result of the power element? Yes and no. Because players are across the board serving bigger, hitting harder and punishing their bodies in the process, they are ridiculously susceptible to getting hurt. But I think it is more than the power of today’s players— it is their athleticism that creates some of the problems. By and large, they cover the court with more alacrity, they have to change direction and recover during points to a greater degree than their predecessors, and it all takes it toll. Did Hingis have to leave the game terribly prematurely at 22 because of the power she confronted in her adversaries, or was she poorly advised on shoe equipment and training techniques? Do Venus and Serena suffer with their physical maladies because they have not trained the right way or because of the violent nature of their stroke production? Do open stances compound the problem for some competitors since they are forced to play the game that way to counter the big hitting of opponents?

Frankly, I don’t have all the answers. But I do feel that there are many highly appealing players who have graced the game in recent years. Pete Sampras was a joy to watch because he had sparkling all around talent, a brilliant running forehand, superb touch and punch on the volley, a spectacular leaping overhead, and, of course, an incomparable serve. But the beauty of his serve was not that he could deliver it at 128 MPH with regularity or 136MPH when he needed the extra pace. It was the fluidity of his motion, his uncanny placement, and his grace. Roger Federer is great to watch now as he moves through matches almost effortlessly and combines power with great touch. He, too, has the whole package. Agassi endures because he has such excellent stroke production off both sides and a very good tactical mind. Roddick is celebrated for the brutality of his game but he mixes in the slice backhand to back up his two-handed drives, he tries to come in more when it behooves him, and he thinks his way through a lot of matches. Lleyton Hewitt is a thinking man’s player who spent two years in a row at No. 1 without much power in his game.

Among the women, the trend toward big hitting is in some ways more worrisome. Watching either Williams sister against Davenport, it becomes essentially a slugfest. Henin-Hardenne and Clijsters need to come back into the picture since they rely much more on quickness and sound stroke execution than power. Sharapova at the moment is following the trend of explosiveness from the baseline, but in the long run she will hopefully display more diversity. I hope that happens because, at the moment, the men have more variety in their game than the women. Either way, there is no shortage of injuries in either tour, and that is worrisome.

Chris Evert played the game just the way she should have for her time, and toward the end of her career she demonstrated with her win over Seles at the Open that she could cope with the emerging power brigade. Did the sport not expose her to injury? To some extent, but she had something to do with it as well. Her superb footwork and balance and the unimpeachable fundamentals of her game served her well, and she knew when she needed to take time off and rest. I have a feeling she might have avoided many of the injuries today’s player are experiencing because she took such good care of herself and she was so smooth on the court.

Q-17: Chris was enormously committed to the development of the  sport, on and off court. But even for one as focused as she, how do you think it would have distracted her from those priorities in tennis, and her longevity of passion for the sport, had she lived in a world so booming with money that you earn $1 million just for winning the US Open, when Chris won less than $9 million (purely tournament-earned) in her entire career?

sport, on and off court. But even for one as focused as she, how do you think it would have distracted her from those priorities in tennis, and her longevity of passion for the sport, had she lived in a world so booming with money that you earn $1 million just for winning the US Open, when Chris won less than $9 million (purely tournament-earned) in her entire career?

This issue also relates to media-invasiveness. I cannot envision Chris Evert allowing a camera crew to follow her into the dressing room  and in her limo prior to a match…I imagine she would have considered that a bit unserious and undisciplined, and I see her being horrified had someone dare suggest to allow a camera to turn her private pre-match meditation time into a media spectacle. Are the worlds of today’s tennis and that of the 70s/80s THAT far apart in mentality as they appear?

and in her limo prior to a match…I imagine she would have considered that a bit unserious and undisciplined, and I see her being horrified had someone dare suggest to allow a camera to turn her private pre-match meditation time into a media spectacle. Are the worlds of today’s tennis and that of the 70s/80s THAT far apart in mentality as they appear?

SF: It is indeed a different world, and it would have been interesting to see how Chris would have reacted if she was playing nowadays. Perhaps she would have let a camera follow her in the locker room before a match if it was expected of her, if it was essentially a requirement. The world has changed, tennis is not the same, and Chris would have come to terms with that. But she would never have allowed any of the hoopla to distract her from her primary goals, or diminish her professionalism.

It is absolutely true that the money has exploded in tennis, but the prize money figures escalated dramatically from the time Chris turned pro in 1973 to when she quit in 1989. Once more, I am convinced that with her mentality and purposefulness, Chris would have not allowed the exorbitant prize money to blur her view of the big picture. She would have realized that winning major titles translates into big dollars and endorsements, and would have kept going about her business sensibly and methodically.

Q-18: As there are different approaches to psychology—Freudian, Jungian, Adlerian, Rogerian— so there is an Evertian approach to this sport. Her match play was artful because she ENJOYED working for a point, didn’t want to win without working hard to earn it, and could use every shot and angle known to tennis in a single rally. She didn’t ace her way to her results; it was so much more admirable than that. Indeed, many of her losses showed her high dignity and championship quality more than many victories, and that cannot be said of many who play the game.

There are articles that say Chrissie is fighting a “quiet culture war” with her tennis academy, trying to keep alive strategy, sportsmanship, and mental fortitude. But do you feel there is any way to profoundly elevate the mental and chess-like aspects of the game, at the pro level, that made Chris so phenomenal, considering its current direction?

SF: I remain optimistic that the “Evertian approach to this sport” will not disappear. Clearly, Martina Hingis represented many of the best Evert qualities of plotting points intelligently and artfully, of  forcing others to play matches on her terms, of demonstrating that brain can win over brawn in many cases. Henin-Hardenne could turn out that way as well if she can get her health back. Federer is very thoughtful, too.

forcing others to play matches on her terms, of demonstrating that brain can win over brawn in many cases. Henin-Hardenne could turn out that way as well if she can get her health back. Federer is very thoughtful, too.

The game goes through all kinds of phases and directions, and changes considerably every decade. While there might not ever be another player who plays the game and thinks about it quite like Chris Evert, we will see players of her ilk again.

As for the so-called “quiet culture war” you mention, I am sure Chris will prevail on that count by the force of her example and the inspiration she provides for so many champions in the making.

Q-19: Here’s the bubble-gum question. Many of us who have seen Evert’s early matches, up until 1974, notice she seem to be nibbling away at some gum while playing matches, Wimbledon included. Do you know what ended this practice, or if people worried she would swallow the gum while running? It comes off as a bit punk and defiant. But it seems more likely just being school-girlish at the time and that she was just being a gum-chewin’ kid.

SF: Chris was 16 at her first U.S. Open when she made her scintillating run to the semifinals, and chewing gum was one of her trademarks. I think it helped her deal with playing on such a big stage for the first time. She did continue to chew the gum for a few more years, but there was no great symbolism surrounding it. She was an American teenager, and many of the kids who watched her surely felt it was “cool” that someone so composed and mature would chew gum in the public arena. It was just part of her personality at the time and no one really talked about it much.

Q-20: And finally, I get much correspondence at ChrisEvert.Net from people who discovered Chrissie as late as 1987 (and even 1989!!!) who continue to pursue knowledge of her career and who watch and collect her matches with great zeal to this day. I am, myself, almost taken aback with surprise by this fact, but the fact remains. Knowing how remarkably charismatic Evert was, does it surprise you at all to know that, even at age 33 and 34, her on-court presence was so striking that she was still wracking in new fans, and that after all this time, so many people still remember the “Legendary Battles of Xena” (that’s Chris) like they were in the latest morning’s newspapers?

SF: I find it absolutely remarkable that so many of the people who correspond with ChrisEvert.Net discovered her so late in her career. Too many great players are swiftly forgotten or overlooked once they have retired, but Chris was immensely popular and gracious with the fans, the media and everyone connected with tennis that her appeal has deservedly kept her around much longer in the public consciousness.

No other champion won and lost with such equanimity; no one else demonstrated as much dignity over a long span; no one played top level tennis for longer. She emerged as an unflappable teenager and became a household name at 16. From that juncture on, people were drawn to her because she had so much class and character, because she handled arduous losses with unmistakable grace, because she refused to gloat after her most cherished triumphs.

Chris Evert was and is one of a kind. So how can I be surprised that so many fans flocked to her late in her career and so many people remain devoted to her today? She deserves all of it.

Editor’s Note: Make sure to read up on more from Steve Flink at his new site!

(c) 2003/16 chrisevert.net