“For seven years, she was Queen of the Courts, ruling the Tennis Throne…”

Chris Evert was born on December 21, 1954 in Fort Lauderdale, Florida and was hitting tennis balls across the public clay courts of  that city by the time she was only five years old. Her father, Jimmy Evert, was working 7 days a week as the tennis pro at Holiday Park (since renamed the Jimmy Evert Tennis Center) and looking for ways to be closer to his children. Tossing tennis balls out of a shopping cart, he taught little Chrissie and her four siblings the basics of tennis, with hand-me-down racquets.

that city by the time she was only five years old. Her father, Jimmy Evert, was working 7 days a week as the tennis pro at Holiday Park (since renamed the Jimmy Evert Tennis Center) and looking for ways to be closer to his children. Tossing tennis balls out of a shopping cart, he taught little Chrissie and her four siblings the basics of tennis, with hand-me-down racquets.

“I remember him saying ‘Racquet back, turn sideways, step in when you hit the ball’ and I remembered those three fundamental things forever,” says Chrissie in retrospect.

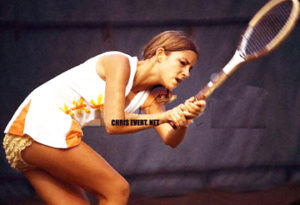

Another thing he taught her, which later became a trademark shot that influenced generations of players to emulate her, was the two-handed backhand. A powerful drive shot, the two-handed was supposed to be a temporary compensation, Jimmy Evert says, “because she was too small and weak to swing the backhand with one hand. I had hoped she would change.” And she did. Not the stroke, but the way tennis was played. (Today, over 80% of the top 100 pros use a two-handed backhand.)

Indeed, a fine teacher he must have been, because all 5 of his children went on to win National Juniors Championships. But part of the Evert children’s tennis success had to do with having each other to play with. “Having siblings definitely helps you improve your game,” Chrissie says, “Just look at the McEnroes and the Williamses – of course, it helps.”

For one thing, it made her mentally stronger having to compete with her sister, who she didn’t like to beat. “She had to focus on playing the ball instead of her sister,” says sister Claire Evert. If she could focus only on the ball, then her sister could become just another player, and then she could block out any other distractions to focus on winning every single point. “One thing that makes Chris such a great champion,” Billie Jean King said, “is that she doesn’t play games or sets, she plays points.”

Her extreme ability to isolate each individual point helped build a very tough killer instinct. Chris once distilled the ‘killer instinct’ to its basic roots, defining it simply as “feeling that, at that moment, there is nothing in the world more important than winning the next point.”

Having a father be the local teaching pro, with constant access to nearby tennis courts and sibling players to hit and compete with, was the first stamp of destiny in the Chris Evert story. But certainly the second was in going to a tennis clinic given by Maureen Connolly (the Chris Evert of her era) when Chrissie was just 10 years old. Evert got to hit with Connolly, who afterward mentioned positive aspects of Chris’ (very early) play as an example to the other kids. Like a Nod from one of the Great Elders, this inspired young Chris to keep moving forward with full belief in the possibilities the game of tennis had to offer her.

And by the 8th grade, through hard work and endless hours of dedication and sacrifice, Chrissie had matured into a focused competitor, and became the #1 nationally ranked player in the Girl’s 14-under Division. “As soon as you win that first trophy or tournament, it’s all worth it,” Evert said. “You feel great about yourself. Tennis helped give me an identity and made me feel like somebody.”

This feeling can only have increased when, a year later, in 1970, 15-year old pony-tailed amateur Christine Marie Evert bounced into a small tournament in North Carolina and defeated the number one ranked women’s professional player in the world, Margaret Court, by the score of 7-6 7-6. Court had just recently completed her Grand Slam (winning all 4 Grand Slam singles titles in the same calendar year), a feat that had been accomplished only 5 times in the history of the sport. It was the first tournament Chris had ever gone to without her parents. When she phoned her father to tell him what had happened, he fell on the floor and needed to be told 4 times before his ears allowed the news to reach his brain. Understandably, this is still one of Chrissie’s most cherished wins.

The kid had arrived. But there were greater arrivals up ahead.

Next arrival: Forest Hills, 1971. It was the US Open, one of the “Big Four” on the Pro Tennis circuit, and Chrissie’s mother, Colette, came along to keep her daughter company. (Little did she know that this would become a full-time job for the next 20 years!) Still an amateur player, Evert barreled through to the semifinals of the 120-player Grand Slam tournament, upsetting 3 seeded players on the way, and becoming the youngest player ever to reach the semifinals of the US Open, and the first 16-year-old to do so in 20 years; the first, in fact, since Maureen Connolly.

“All of the ladies I beat that year at the Open left the court in tears,” Evert remembers of her walloped opponents.

“Back then, there weren’t several (players) that were 14, 15, 16 years old,” Colette Evert recalls. “Chris was the only young one on the tour.”

It was certainly her age, but more so her resolve (and all the upsets she caused!) that catapulted young Evert into national public awareness. “You could not put Evert anywhere but in the Big Room, from the very start,” says Bud Collins, the NBC commentator for the 71 US Open. “The network realized immediately she was going to draw a crowd.” From the 2nd round, all of Evert’s matches were played on Center Court.

She finally lost in the semifinal round to the #1 seed and eventual champion, Billie Jean King. But she returned to her high school classmates in Fort Lauderdale, a heroine. And like an inclandestine first meeting with the future love of your life, Evert had likewise let the whole tennis world know that there was a new girl in town. From this first appearance on the scene, Evert would thrill crowds in stadiums across the globe with her perseverance, bravery, and perfect court demeanour, which set a standard of placing personal integrity on par with the value of winning in defining the heart of a champion.

Jimmy Connors was the first to reach the heart of the champion, becoming engaged to Chris in the Winter of 1973. Chris Evert and Jimmy Connors were young, attractive, in love, and both at the top of the tennis world, each winning the respective men’s and ladies’ Wimbledon 1974 Singles crowns. They shared the Champion’s dance and made headlines about “The Love Match” the world-over with their wedding engagement announced for October. Then, the fairytale engagement was called off, although they did stay together and became re-engaged.

But by early 1976, all bets were off. The desire on both of their parts to be number 1 in the world was greater than their desire for either to give up their careers for domestication. The time (and separate world travel) necessary to reach their goal of being world champion competitors demanded a sacrifice, and in this case, it was each other.

“If I were to pick a first love, he would definitely be my pick,” Evert says of Connors, even 25 years later, “because a little bit of that influence stays with you throughout your life.”

International Tennis writer Peter Bodo says of the pairing, “It was a match made in Heaven, not on Earth, which is probably why it didn’t last.”

Meanwhile, Evert had turned pro in December of 1972 on the occasion of her 18th birthday, and at that time signed a contract with Wilson tennis racquets on her parent’s front porch. Neither Chris’ nor Wilson’s loyalty to each other ever swayed throughout her entire professional playing career, until the very last ball was struck at the end of the 1989 Federation Cup finals victory over Conchita Martinez.

At the close of 1974, Evert had become 1 of only 3 players (with Court and King) to ever win 100 matches in a single season, a record which still stands today. The following year, she was only 6 matches shy of repeating the feat. Also during her mammoth 1974 season, she won 55 consecutive matches, a record which lasted 10 years. And the winnings were dizzying. She won Wimbledon in 1974, 1976, and 1981. She won the US Open 6 of 8 years between 1975 and 1982, and at one point won four consecutive (1975-1978), becoming the first woman since the 1930’s to do so. She won a record 7 French championships beginning with back to back titles in 1974 and 75, and took the Australian Open title in 1982 and 84. But of her 18 Grand Slam singles titles, it is the second one, following the French title, at Wimbledon 1974, that a daughter’s father would remember the most.

While Jimmy Connors’ eyes had been firmly fixed on Chris during the Wimbledon 74 finals victory, father Jimmy Evert was at home in Fort Lauderdale, because he got too nervous from the tension of watching his daughter’s fate hang in the balance, from point to point, when she played. “There was no live TV in 1974,” Jimmy Evert remembers. “She was to call right after the match. So just about an hour had gone by and the phone rings. I pick it up and I just hear this little voice say, ‘I won!’ and I was silent. So Chris said, ‘Dad, are you alright?’ But I was so choaked up. Just imagine your 19-year-old daughter calling you from England telling you that she had just won Wimbledon.”

Being dubbed “The Ice Princess” & “Ice Maiden” by the English press when she arrived at Wimbledon in 1972 as a school girl, all the winning came with a price. At the time, the term suggested that Chris was somehow cold, ruthless, and heartless – which she absolutely was, on court. But when her underdog status changed to being the number one player in the world, as she was in 1974, 1975, 1976, 1977, and 1978, the crowds “cooled” on Cool Chris.

But the victories continued, especially on clay, where she won every match she played over a 6 year period, covering 125 straight matches in 24 tournaments.

“I was hungry to win every point,” Evert says. “It was all about ‘What am I going to eat before my match, how much sleep am I going to get, who am I going to beat?’ ”

In 1976, Evert became the first tennis player to reach the $1 million mark in career prize money. That’s without having collected her earnings prior to 1973 when she played as an amateur in order to finish high school.

When she won the 1972 Slims Championships at 17, for instance, she had to decline $25,000 prize money, which was quite a huge amount back in 1972, if you’re not the type to think it’s a lot today.

The gruel of life on the tour definitely affected Chris emotionally, but she kept it out of her tennis for the most part. Her high visibility as the world’s top female athlete brought some high-profile romantic interest, but not without an equal level of complication. From the (then) President’s dashing son, Jack Ford, to the heartthrob who was the top movie Box Office star 5 years in a row, Burt Reynolds, dating opportunities were intriguing, to stay the least. But being naturally shy, and having paparazzi hounding every interaction on a perceived date, was a formidable roadblock to being open and able to connect. Life off-court was far more difficult to give form to than those well-constructed points on court.

But in 1978, she had the good fortune to read an article about how lonely life was on the tennis tour, which was written by a stunningly handsome English male player. His name was John Lloyd. They met, found an instant chemistry existed between them, and were quite serious about their romantic involvement by the time Wimbledon rolled around later that summer.

Chris played some uncharacteristically nonchalant games near the end of the match in the finals, and allowed Martina Navratilova to climb back into contention late in the 3rd set after being up 4-2, and lost the title 2-6 6-4 7-5. Lloyd naturally expected Chris to be too upset to go out for dinner that night, as they had planned, but when Chrissie said, “Are you kidding? Of course I want to go out!” he knew it must be love.

The couple married in April 1979.

John Lloyd took over coaching duties of his new wife, relieving father Jimmy Evert of his previous post. And with the distractions of a life outside of tennis, there was an adjustment period which included relinquishing the number one ranking to Navratilova in 1979, losing a string of matches to hungrier rival Tracy Austin in a short span (3 times in 11 days), and of not being particularly pleased with her play. So after taking a few months off in February and March of the 1980 season, Chris gained a new awareness of choices.

She didn’t have to play tennis out of necessity, because she could just as easily settle down with John. But she knew the choice she wanted to make was to play, and realize her potentials as an all-time great champion. No longer from necessity, but from desire. Chris Evert-Lloyd, as she was to be known, took the French and US titles that year, and by the end of 1980, became number 1 in the world again, where she remained until May of 1982.

One of her major wins during that long string of 18 months at the top, was probably a bit of a mixed blessing. She had already made a fair habit of beating rival Martina Navratilova since their first meeting in 1973, but in 1981, having won by double their head-to-head meetings, Evert handed Navratilova the heaviest humbling of her career, 6-0 6-0 in the Amelia Island finals in front of a nation-wide audience on NBC TV.

This shook Martina, who had already taken large strides to become a more physically fit player and improve her consistency in vying for the number 1 ranking. But now she really had to face that finishing the job meant building her mental confidence, stamina, and clarity. And it was her destiny to do this to a degree that would forever change the world of women’s tennis.

The change in Navratilova was likewise to bring about the greatest challenge to Evert’s identity as a champion. Martina was two years younger, had switched to graphite while Chris still paddled away with her Wilson wood, was in the best shape a female athlete had ever been in, and as tennis analyst and commentator Mary Carillo put it, “Chris can take a perverse pleasure in the fact that the architects that designed Martina’s game had Chris’ (game) in mind.” Martina was specifically gunning for Chris, and was hungry for the kind of dominance that Chris had already been enjoying for the last 10 years.

Martina completely dominated women’s tennis from 1983 through 1984, handing Chris a daunting 2-year draught in their head-to-head meetings, with Martina winning 13 consecutive matches. Evert had beaten Martina in 15 of 17 matches between the Spring of 1975 and the end of 77, but losing in that manner was completely alien to Chris. And to see Chrissie lose in that manner, completely alien to tennis audiences! However, 13 did prove to be the unluckiest of numbers, even for one of Navratilova’s stature, as Chris was to break the chain of loses in their next meeting.

After a near-win in the 84 US Open final against Navratilova 4-6 6-4 6-4, the 13th consecutive loss, the two rivals played in an exhibition match in San Diego, and Chris charged net at every opportunity, beating Martina with conviction, 6-2 7-6. As the 1984 season closed, with the Australian Open, Evert won her 1000th career match, the first player ever to do so, and then won the title, furthering her string of consecutive years winning a Grand Slam event to 11; a string that would reach a record 13. (Perhaps 13 is a number that always plays the role of streak-ender!)

In any case, it all represented a change in fortune for Evert. She next met Martina again in January 1985 at a tournament in Key Biscayne, and this time it was not an exhibition, but for the record: She won in even more convincing fashion, by the score of 6-2 6-4 in a swirling wind on hard court surface, and the drought was officially broken.

Then, four months later, in June, Chris took her second Grand Slam in a row, again beating Martina in one of the most dramatic and well-played matches in women’s tennis history, this time on clay courts, winning the French Open 6-3 6-7 7-5.

This victory tied Chris for the all-time record for victories at the French (She broke the record the following year, beating Martina again 2-6 6-3 6-3 in another long, dramatic final for her 7th French crown), but in addition, Chris regained the world’s number one ranking back from Navratilova.

“Many people missed what that match meant. It wasn’t just that Chris had beaten Martina again or had won another Grand Slam,” tennis analyst and coach Andy Brandi was to say at the time, “It was so much more than that: The Queen was back on the Throne. There wasn’t a dry eye in the place.”

Indeed, that was the romance of it, and Chris would hold the #1 ranking until the end of November that year. It would be her final stay at the top, at age 31. But in terms of solidifying an image of accomplishment achieved against the most daunting odds, the Throne was forever hers. Adding honor to achievement in 1985, the Women’s Sports Foundation named Evert the Greatest Woman Athlete of the Last 25 Years.

While Martina Navratilova and Steffi Graf would each hold the #1 ranking until Evert retired, she played both players almost evenly from 1985 to her retirement in 1989, even while being 2 years older than Navratilova, and nearly twice Graf’s, with a game that relied on mental consistency (which would deteriorate with age much quicker than would the physical side of the game.) And admittedly, and happily so, by 1987 Chris had plenty of off-court distractions that removed some of the tunnel-vision that defined her Ice Maiden years.

Still Chris was inevitably thankful to Navratilova for the great struggles of their rivalry because it prolonged her career, gave her something to strive for, and – while Chris pushed Martina to develop the mental side of her game, and improve her patience and ground strokes, to reach greatness – Chrissie would implement a dietary regimen, physical training program, and even switch from her wood racquet to try her hand at both a harder graphite racquet and a more insistent net game to keep up with Martina’s pace. For some insight into her admirable fighting spirit, when she switched from her wood racquet to graphite, she was already the age at which Steffi Graf retired from professional tennis.

Dennis Ralston, who had been John Lloyd’s coach, also became Evert’s coach in 1982 when Chris was initially having problems facing Navratilova’s power tactics. “The only way you’re going to beat Martina is by taking the net away from her,” Ralston would tell a reluctant net-rushing Chris. But indeed Ralston “made me a better volleyer – more touch, softer hands,” Evert says, “and helped me with my kick serve.”

Another great thing to happen to Evert through her association with Navratilova was to meet her husband of 18 years, Andy Mill. Chris and John Lloyd called their marriage quits late in 1986, Chris says, because of her own stubbornness in her commitment to her tennis, which kept them apart. “Absence does not necessarily make the heart grow fonder,” she would say, while acknowledging that all the responsibility for the divorce was on her shoulders. Like with Jimmy Connors before him, Chris had ultimately chosen tennis as her first passion, and said flatly, “John was perfect. The relationship suffered because I didn’t have enough left (after tennis) to give. That’s when we grew apart.”

“My parents weren’t speaking to me because they love John so much,” Chrissie reveals, “and I was the bad guy.” So, says Chris, “ It was December 28th, 1986, and Martina had kept asking me to go to her house in Aspen, Colorado, so I did it to get away. We went to a New Year’s Eve party, and that’s where I met Andy.”

Andy Mill was a dashing US Olympic downhill skier, and the local skiing pro in Aspen. “Chris was the worst first time skier I’ve ever experienced, with the exception of maybe Reggie Jackson,” Mills laughs.

“He skied backwards and held my hands all the way down the mountain,” Evert says. And indeed he did, helping the woman who perfectly played the role of a Great Queen to tennis history with dignity and grace, down from her perch atop the Throne of her sport and into her new life, with a gentle, convincing, and reassuring presence that made, what would have been a very difficult transition to make sense of, a fairly easy and natural shift of lifestyle. They married on July 30, 1988 and had 3 children after Chris retired from competitive play in 1989.

When Evert beat Navratilova in a dramatic 3-6 6-1 7-6 victory in Martina’s second-home state of Texas in the 1987 Virginia Slims of Houston final, it was the very first tournament she played in without the Lloyd affixed to the end of the legendary name of Evert. “Game, set, and match, Chris Evert” had been heard for the first time since the 1970’s.

Chris Evert’s final tournament match victory came at the 1989 US Open, the place where her fame began, beating Monica Seles 6-0 6-2 in what was one of the cleanest, most punishingly well-played matches of Chris’ 20-year career. Then, with straight sets wins in all of her Federation Cup singles matches, Chris closed out the Evert Dynasty and completed her stint as Queen of the Courts with the highest winning percentage, male or female, in tennis history.

“I’m so glad I came along when I did,” Chrissie now says, “with Arthur Ashe, Billie Jean King, Stan Smith, as role models. And alongside me was Bjorn (Borg), Jimmy (Connors), and Martina. It was the tennis boom. It was personal, we were close to our fans, we had enough money. Now it’s just a lot different. It’s probably more professional but I don’t see the friendships, I don’t see the bonds. I don’t see the intimacy that we had.”

“Chrissie was a beautiful woman playing a beautiful sport in a beautiful way, and that’s why America fell in love with her,” said Tom Friend of the Washington Post. But the love and admiration for Evert was definitely felt in every country in the world, perhaps summed up best by International Tennis Federation Vice President, Brian Tobin, who said of Evert, “She is not only the lady champion, but a champion lady.”

In 1995, Chris Evert was the fourth player ever to be elected unanimously into the International Tennis Hall of Fame. She was the sole inductee for that year.

(c) 2003/16 chrisevert.net