Every sport needs rivalries.

Every sport needs rivalries.

The great rivalries create anticipation for the fans and the players alike, raise awareness about the sport to new audiences as people hear about the titanic clashes in their local sports pages, and in the most classic of pairings, the rivals may even represent opposing forces in the universe.

Sometimes, the rivals raise the very standards of the sport, as each player works to better themselves in order to gain an edge on the rivalry and show, in short, that they are the greatest at their craft.

Boxing had Ali and Frazier, golf had Nicklaus and Palmer, baseball had Williams and DiMaggio, the NBA had Bird and Magic, tennis has had Borg and McEnroe, and more recently Federer and Nadal, but it also had the epic rivalry of Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova. To gain some perspective, Borg and McEnroe played 14 times, Chris and Martina, 80.

Called “The Rivalry of the Century” by sports writer Bud Collins, it stretched from 1973 to 1988, and is thought by many to be the greatest rivalry in the history of all sports.

“No two competitors have ever competed against each other as much as Chris & Martina. It will never happen again… 80 times?

Which 2 boxers, which 2 baseball teams, which 2 anybodies, are ever going to play each other 80 times over 18 years with such high quality stuff?” asks broadcast sports analyst Mary Carillo.

Their rivalry was intensified by the fact that, while their personalities were  a study in contrasts, so too were their playing styles representative and magnifications of those differences. Evert, the picture of consistency and patience, impeccably placed ground strokes, and an iron will that got stronger with added pressure.

a study in contrasts, so too were their playing styles representative and magnifications of those differences. Evert, the picture of consistency and patience, impeccably placed ground strokes, and an iron will that got stronger with added pressure.

Navratilova, the emotional, volatile, relentlessly & gracefully aggressive warrior, attacking at every opportunity, and arguing line calls while joking with fans.

“Her fans appreciated what she stood for and my fans appreciated what I stood for,” Evert said. “It was about how we looked, how we acted, our style, where we came from.”

Through the roots of these differences flourished a remarkable symbiosis, challenging each other with the improvements every season seemed to bring to their play, and thereby broadening the other’s game in the process.

“As they raised each other’s game, they raised the whole sport,” observes Carillo.

Indeed, once Billie Jean King got the ladies’ pro tour on its feet, these two champions carried the entire burden of its future squarely on their shoulders for over 10 years. To be considered a great success, a tournament needed either Evert or Navratilova – or both – in its draw.

The rivalry even had a fair dose of camaraderie: Evert & Navratilova won the 1975 French Open and 1976 Wimbledon doubles championships together; the master of the baseline teamed with the serve-and-volley dervish, in what surely seems in retrospect an almost unfair alliance. And as rivals go, they were really very good friends.

But it would be disrespectful to the completeness and complexity of the rivalry to smooth over the rough spots, for there were a few terse years.. It was not all glorious play & sportsmanship.

The rivalry had its divisive side, most notably spearheaded by Navratilova’s coach in basketball player Nancy Lieberman, later adding Renee Richards, who would teach Martina to gain the edge on Chris in the early 1980s by focusing on hating her. By her own admission, she would visualize seeing Evert as “the enemy” during her acclaimed physical fitness training workouts. And for at least two years in the early 80s, they were barely speaking.

in the early 1980s by focusing on hating her. By her own admission, she would visualize seeing Evert as “the enemy” during her acclaimed physical fitness training workouts. And for at least two years in the early 80s, they were barely speaking.

“Chris can take a perverse pleasure in the fact that the architects that designed Martina’s game had Chris’ (game) in mind,” Mary Carillo notes. “Chris had such fine ground strokes and incredible passing shots off both sides.”

While Chris had asked for distance within the competition in the late 1970s after their doubles successes together, because she wanted to remain more of a mystery to Martina in their singles matches, it didn’t create the same level of friction, because there was never personal dislike being communicated between the two players.

Evert never fueling any hatred for her opponents; she just challenged and bettered herself, and the results followed naturally. Likewise, Bill Russell spoke eloquently about his rivalry with Wilt Chamberlain, saying, “We didn’t have a rivalry; we had a genuinely fierce competition that was based on friendship and respect. We just loved playing against each other. The fierceness of the competition bonded us as friends for eternity. We loved competition.”

Aside from palpable distaste for the other expressed in rivalries like that of Americans Jimmy Connors and John McEnroe; two bad boys from the same country, vying for the top spot while not appreciating the other’s form of brashness and match distraction tactics, there wasn’t much bad blood in the sportsmanship-dominated world of tennis. And these were simpler times on the pro tour, when players had one coach and often traveled alone to tournaments. So in what was then considered a bold move, Martina organized what came to be popularly known as “Team Navratilova” to devise the strategy and tactics, psychological and physical, to confound Evert’s game. And impressively it worked for a record 13 consecutive matches between 1983 and 84. (The success of which, to Martina’s eternal credit, revolutionizing the way all pro players approach the sport, with full teams and entourages, ensuring the best chance for success.)

While these tactics created frictions outside of the results, Chris certainly understood the need for certain barriers within a rivalry like theirs. “It’s very hard,” Chrissie says, ” when you (both) want to be #1. You don’t want emotionally to get into somebody’s head when you’re competing with them and you don’t want them to get into your head, either.”

As Navratilova became more assured of her undeniable and lasting impact on tennis history, and once both Chris & Martina had to face the changing of the guard together at the hands of the young Steffi Graf, the profound ties of their united history and friendship came back into view for both of them, and deepened into the friendship it had begun as.

It is interesting to note certain trends in Navratilova and Evert’s head-to-head clashes. In their first 50 matches, Martina won 20. But a full 18 of the 20 wins were on grass and indoor carpet. Grass was Martina’s best surface, perfect for her style of play, and Indoor Carpet produced –by a dramatic 4 times any other surface– Chris’ career losses. This certainly did not discourage her from playing the indoor circuit, despite the lopsided loss percentage, but at least on grass, clay, or hard court, Evert’s results show she was seeing the ball much better and was at least producing the kind of tennis she is naturally capable of.

At the end of their careers, it was the same story: Their last 8 matches, Martina won 5, all of which were either indoor or on grass. Chris won both hard court duels and the 1 clay match they played, losing only 14 games to Navratilova in all 3 matches combined. Certainly the latter part of the rivalry showed their competitive level had evened out. Between their last appearance in a Grand Slam final (1986 French) and their last meeting in a Grand Slam level event (1988 Wimbledon), they split those 10 matches, 5 a piece. It seems fair enough to look through that lens, as Evert was retiring from a clear decline in her play at age 33 to 34, and after that ’88 Wimbledon, she married Andy Mill and won only 1 very small tournament for the rest of her career, and was no longer playing representative tennis: It was not just Navratilova she was losing to, but players like Raffaella Reggi, Natalia Zvereva, Barbara Paulus & Anne Minter, who she would normally handle without significant struggle. Meanwhile, Martina played competitively until 1994.

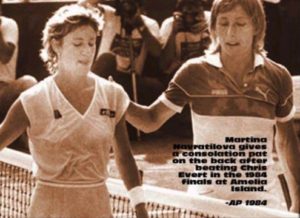

Over all, Navratilova held a 43-37 edge (a 3 match difference), but there, again, there are subtle factors in the composition of the matches, and the surfaces they were played on, that could have caused the win/loss ratio to go in other, equally closely contested, directions. Chris played Martina on Chris’ worst surface (Indoor Carpet) more than any other surface. Meanwhile, Martina only beat Chris on clay 3 times in 16 years, and that also represents a big part of the missing statistics: Navratilova skipped most of the clay-court tournament seasons, taking that time to recharge & sharpen her game. Indeed, after two sound defeats on clay in 1975, Navratilova did not challenge Chris on European clay until her return to Paris in 1982. During this period, Navratilova was also absent from the North American clay court season and did not play Evert again on American clay until the final of Amelia Island in the spring of 1981, with Chrissie winning 6-0 6-0. To be taken as a legitimate #1, Navratilova did play a few events in the clay season from 1982-84 (one of which, also at Amelia, allowed Martina to hand Chrissie the worst loss of her playing career, 6-2 6-0, in the ’84 finals) but stayed clear of a rejuvinated Evert throughout 1985-1986 on clay except at the French Open, where Evert won both meetings.

All in all, they played each other significantly more on grass and indoors (40 times) than on clay and Har-Tru clay (13 times), largely because Chris felt responsible –as a major draw for womens tennis–to play during every phase of the tennis season, regardless of how the surface might benefit her or not. That said, it is impressive to note that outside of Martina’s 5-0 dominance in Wimbledon finals, Evert kept steady with Navratilova on grass (5-5) outside of Wimbledon finals.

An additional subtlety to the results of the rivalry is that, Martina’s earlier career inconsistency actually benefitted her head-to-head count with Evert between 1975 and 1981, where she would have likely been the victim of many more matches that Chris was inevitably playing and winning against other opponents who made the final round of competition, instead of Navratilova. Whereas during Navratilova’s equally long dominance, Evert was the more consistent performer, always remaining a firm number 2, inevitably competing in the final stages of any tournament she entered. So while much of history’s perception of Navratilova’s dominance comes from the dramatic impact of her 13-match winning streak against Chris between1983-1984, those two years were unrepresentative yet effected with severity both statistics and perceptions. After all, Evert lost 10 matches to Navratilova in 1982-83 playing with a wood racquet, while Martina competed with graphite.. A disadvantage to say the least. But it was not known at the time what an advantage the modern racquets were providing, and that detail is not part of what’s preserved in public memory.

To Martina’s unquestionable credit, her 10-4 record versus Evert in Grand Slam finals also shows her ability to rise to the higher level on the grandest of occasions. And that rightly pushes perception in her favor, for being the best player in many people’s minds.

In the end, these two players were probably more closely matched against each other and above the rest of the field for as long a period of time as any two competitors could be, and all 16 years considered, possibly dead even.

In the end, these two players were probably more closely matched against each other and above the rest of the field for as long a period of time as any two competitors could be, and all 16 years considered, possibly dead even.

The “Who Was Better” debate will go back and forth with as many twists and turns as the competitor’s dizzying points were played. And ultimately, the answer still relates more to whatever the viewer thinks matters in a tennis player, how the game should be played, and what you find beauty in. As the story says, they represented polar opposite extremes.

“But I think in the end,” Evert reflected, “we both realized that we pushed each other and made the other one a much better player.” More emphatically, says Martina, “There never will be another Chris and Martina show. There never was another like it and there never will be another.”

They finished their careers tied with 18 Grand Slam singles titles each.

They also finished their careers as friends. Evert even met her husband of 18 years, Andy Mill, while visiting Martina’s home in Aspen Colorado for a New Year’s party.

They were inextricably entwined throughout their playing careers, so it was somehow fitting that when the two players retired, they both chose to settle in Aspen, where Martina lives regularly, and Chris takes a summer home.. As Evert joked at the time, “We just can’t seem to shake each other.”

The greatest rivalry in the history of sport

Martina Navratilova and Chris Evert, enjoying Wimbledon from their seats in the audience, 1999.

WATCH Trailer from the ESPN 30 for 30 Documentary UNMATCHED

READ MORE on the rivalry HERE in this exclusive interview with ChrisEvert.Net & author of “The Rivals: Chris Evert and Martina Navratilova,” Johnette Howard.

(c) 2003/16 chrisevert.net